LA1 probiotic strain shows early promise in treatment of IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), an umbrella term that includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, affects 3 million (1.3%) American adults.1 The cause of these autoimmune diseases is unknown, and in some severe cases, currently available therapeutic agents are ineffective. The need to develop new therapies that will provide lasting relief is substantial.

Regardless of the type of IBD experienced, IBD is accompanied by a defective intestinal epithelial tight junction (TJ). This weakens the intestinal barrier function, causing intestinal permeability (leaky gut), allowing bacteria and toxins to travel over the barrier. Previous research determined that if the intestinal barrier is tightened, infection and subsequent IBD is prevented.

A new proof-of-concept study indicates that probiotics may provide a safe, novel therapy for those experiencing IBD.

“Probiotics have always been touted as important bacteria that help promote health in the intestines. The problem is there are so many bacteria,” says Thomas Ma, MD, PhD, professor and Lloyd Huck Chair of the Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, at Penn State College of Medicine and Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. “One bacteria may have a very positive effect. Another may have no effect.”

In an effort to pinpoint which probiotic may provide effective therapy for IBD, Ma led a team through proof-of-concept study research. During the study, they examined more than 20 probiotic strains. The specific goal was to identify which specific probiotic strain — if any — was capable of increasing diminished barrier function and therefore preventing infection. The LA1 strain of probiotic bacterial species Lactobacillus acidophilus was identified as improving barrier function. If proven in clinical trials, the initial findings from this study could significantly improve quality of life for those with IBD.

Why probiotics

Currently, a number of medications, including corticosteroids and immunomodulators, are available and approved for the management of IBD symptoms.2 Unfortunately, long-term use of certain medications comes with substantial risk. Potential side effects include fractures, infections and secondary diabetes. Targeted biologics are also an option, but they can present considerable risks and are cost-prohibitive and often ineffective.

Even after use of multiple medication therapies, patients with Crohn’s disease often require surgical intervention, which also comes with risks.

In addition to available IBD treatment options, probiotics may offer an organic solution that comes with minimal side effects.

“More than 50% of IBD patients have tried probiotics because they’re looking for something natural to take for their condition,” Ma says. “Use of probiotics that is data- and science-driven would ensure patients get the right probiotic and have the best chance at a positive response.”

Probiotic use comes with minimal potential side effects (bloating and/or diarrhea), which cease when use of the probiotic is discontinued.

Lactobacillus acidophilus (LA1)

The specific source of promise

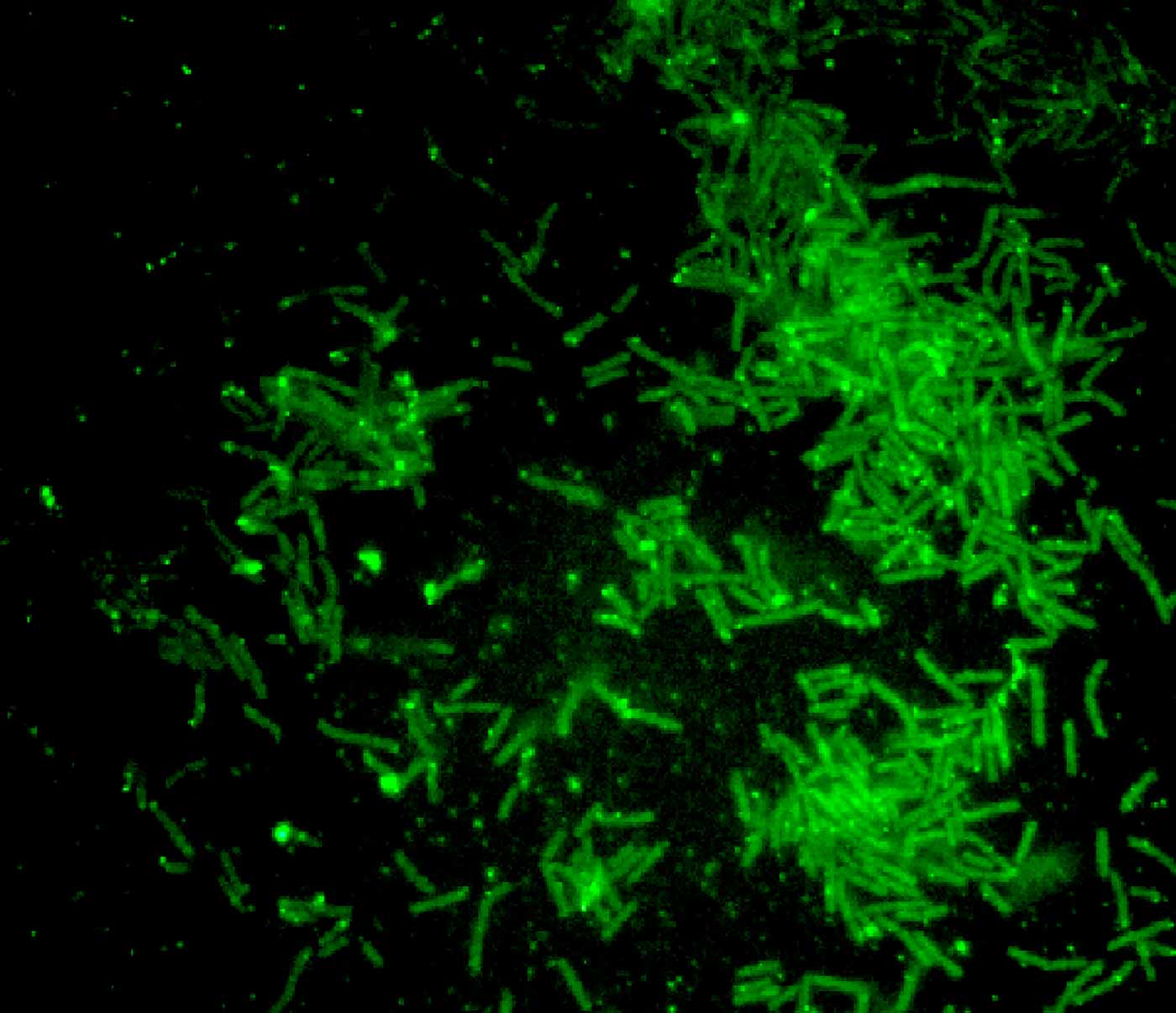

Through their research, Ma’s team evaluated more than 20 probiotics. Though most held no potential, the LA1 strain of L. acidophilus yielded promise in IBD applications. This strain attaches to the apical membrane surface of intestinal epithelial cells in a Toll-like receptor-2 (TLR-2)-dependent manner, activating the intracellular processes that leads to the tightening of the barrier.

In laboratory-grown, human-derived intestinal cells, LA1 quickly improved function of intestinal barrier cells. When performing the study on live mice, LA1 resulted in a significantly tightened intestinal barrier within a single day. This improvement was maintained over the long-term, as long as the probiotic was administered daily.

Additionally, LA1 was found to have preventive properties. Dosing mice with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) resulted in leaky gut within one to two days. Within five to seven days, intestinal inflammation developed, causing DSS-induced colitis.3 By administering LA1 two days prior to introduction of DSS, intestinal inflammation and subsequent colitis was prevented. However, Ma says, “When we disrupt TLR-2, the bacteria are no longer protected against colitis.”

Another strain of L. acidophilus, LA3, had no effect on the ability to tighten the weakened intestinal barrier and did not attach to TLR-2. Other probiotics were screened but had a very modest or no effect.

Looking forward

Focused on the intestinal barrier for more than 30 years, Ma has spent the last decade studying the efficacy of probiotics. The appeal is multidimensional. The bacteria already exist and are found naturally in the gut. As a result, researching probiotics does not require lengthy safety studies, which should speed research along.

There is no LA1-specific probiotic currently available via an over-the-counter or prescription supplement. Most probiotics on the market, which tend to include a mixture of strains, fail to list the specific bacteria included in their products or provide insufficient concentrations of the probiotic needed for optimal benefit. Through current and future research, the understanding of probiotic use could lead to improved outcomes.

“Do I think [LA1 therapy] will be effective?” Ma asks. “Absolutely. The animal studies are compelling, and the promise is there. If someone makes it as a supplement, clinicians can try LA1 probiotics with their patients because it is benign. We’ve found that LA1 improves intestinal permeability, which is an excellent predictor of long-term positive outcomes.”

As with other probiotics, an ideal dose of LA1 is likely between 1 and 100 billion CFUs, with a concentration of 10 to 20 billion CFUs considered a “reasonable dose.” Less than that will have no effect. While probiotic prescription is generally safe, Ma does not recommend modifying patient care at this stage.

Ma recently received FDA approval to study LA1 on an intestinal barrier function in humans. If the research proves the efficacy of LA1, it could be transformative for IBD care.

“Right now, we as physicians don’t have a defined probiotic to use for these purposes,” Ma says. “For most diseases, there is no targeted therapy. We should really be thinking of targeted, evidence-based therapy.”

Learn more about ongoing clinical research at Penn State College of Medicine.

Thomas Y. Ma, MD, PhD

Chair, Department of Medicine, Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Penn State College of Medicine

Professor of Medicine, Cellular Physiology and Molecular Physiology, and Microbiology and Immunology

Phone: 717-531-5018

Email: thomasma@pennstatehealth.psu.edu

Fellowship: Gastroenterology, University of California Medical Center, Irvine, Calif.

Residency: Internal Medicine, Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, New Brunswick, N.J.

Medical School: Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Richmond, Va.

Connect with Thomas Y. Ma, MD, PhD, on Doximity

References

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bowel Disease (IBD) in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/ibd/data-statistics.htm

- Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Medication Options for Crohn’s Disease. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-is-crohns-disease/treatment/medication

- Chassaing B, Aitken JD, Malleshappa M, et. al. Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice. Current Protocols in Immunology. 2014 Feb 4;104:15.25.1-15.25.14. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1525s104. PMID: 24510619