Fertility-Sparing Options for Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. The incidence is increasing, including in premenopausal women.

According to Joshua Kesterson, M.D., a gynecologic oncologist with Penn State Hershey Obstetrics and Gynecology, “Such women may wish to consider fertility-sparing treatment options and avoid standard treatment, which consists of hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and lymph node dissection.”

When considering fertility-sparing treatments, multiple factors must be considered, including the risk of an unstaged cancer, a coexisting cancer, an inherited genetic predisposition to cancer, and the lack of uniformity in medical management of endometrial cancer. When patients move forward with treatment, Kesterson stresses the importance of a thorough pre-treatment assessment, to decrease the chances of an undetected cancer.1

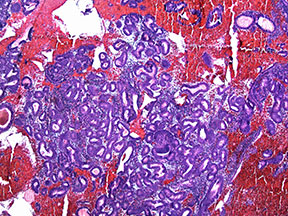

Excess estrogen can lead to hyperplasia of the endometrium, a precursor to endometrial cancer, as seen here with back-to-back crowding of glands.

“I begin each case with dilation and curettage, as both a diagnostic step to confirm the low-grade nature of the tumor and a potential therapeutic benefit from removing the abnormal cells. I follow with an MRI to identify potential myometrial or cervical invasion or lymph node involvement. If there is evidence of grade 2 cancer or higher or metastatic spread, the patient is not an appropriate candidate for uterine preservation.”

“These patients face difficulty conceiving secondary to obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome, and chronic anovulation,” states Kesterson. “We recommend an initial consultation with a reproductive endocrinologist to assess reproductive options and likelihood of conception.”

A subset of pre-menopausal women may develop endometrial cancer due to an inherited genetic predisposition. These women are at risk for other cancers, including colon cancer, and should be referred for genetic counseling.

A majority of selected women will respond to progesterone therapy treatment. However, it is difficult to predict which patients will not respond; therefore, follow-up and reassessment of the endometrium is essential. Treatment consists of a three-to four-month course of oral progesterone therapy, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate or megesterol acetate, which in case series have demonstrated efficacy.

Kesterson notes, “Appropriately selected women with grade 1 endometrial cancer, as well as those with pre-cancerous endometrial hyperplasia, may be candidates for progesterone therapy. These patients usually have irregular cycles and are anovulatory; many are also obese and have been diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Progesterone therapy helps to counterbalance the endometrial effects of excess estrogen, secondary to obesity.”

After hormone therapy, patients undergo a follow-up D&C to ensure the hyperplasia and cancer has reversed. Kesterson explains, “Patients who do not respond after three to four months of progesterone therapy, with D&C evidence of persistence or progression, should undergo definitive therapy, as those who have not responded by then are unlikely to do so. For patients who have responded, I urge prompt follow-up with their reproductive endocrinologist, as most patients who do conceive after uterine preserving therapy require assisted reproductive technologies.”

“We want to ensure optimal outcomes for patients, including those young women who wish to preserve their fertility, through appropriate work-up, patient selection, treatment and surveillance.”

Joshua P. Kesterson, M.D., FACOG

Joshua P. Kesterson, M.D., FACOG

Assistant Professor, Penn State Hershey Obstetrics and Gynecology

Chief, Gynecologic Oncology

717-531-8144

FELLOWSHIP: Gynecologic Oncology, Rosewell Park Cancer Institute

RESIDENCY: OB/GYN, University of Louisville Medical Center

MEDICAL SCHOOL: University of Missouri – Columbia School of Medicine

BOARD CERTIFICATION: Gynecologic Oncology

REFERENCE:

1 Kesterson JP, Fanning J. Fertility-sparing treatment of endometrial cancer: options, outcomes, pitfalls. J Gynecol Oncol. 2012;23:120-4.